Can you treat the guitar like a piano?

When I started playing the guitar, it seemed like the coolest instrument you could possibly play. In some ways, it was like I was more interested in the instrument than music itself. Over the years I’ve gotten obsessed with all kinds of music, including types that don’t really feature the guitar; there have been times where I’ve lost interest in “guitar music” altogether. As I’ve progressed, it’s been less about playing the guitar for me than simply making music. I’ve wondered: can you treat the guitar like it was a different instrument altogether, like a piano?

Something that naturally happens over the course of learning an instrument is: you get a handle on what it can do and what makes it unique, but also, you start to get a sense of its limitations. It’s easy for guitarists to get stuck in a box of familiar licks and “guitar moves” – we end up feeling like we just sound like other guitarists, wondering how we can push ourselves into unfamiliar territory. In this article I’m going to talk a little about just one way I’ve tried to stretch myself and open up my playing.

A lot of great guitarists don’t only study other guitarists, but also vocalists, pianists, horn players, et cetera – this is something you especially hear jazz guitarists talk about. Sometimes we are listening to the way other great musicians phrase a melody, or the kinds of melodic lines or chords they play; equally important is the actual sound, the tone or timbre, of other instruments. Sometimes we get so used to what a guitar looks and sounds like that we don’t ever actually stop and take a closer look at what this thing is and how it, and the person playing it, produces sound. All instruments are inherently limited and possess their own unique characteristics, so it can be instructive to consider what are the natural limits of the guitar and how those compare to other instruments.

I’ll give an example. Because the guitar only has six strings, it can’t play as many notes simultaneously as the piano. Pianists can play as many as ten distinct pitches at once with their fingertips (more if they play multiple keys with each finger!). Also, guitarists are somewhat limited by the way the guitar is tuned and the range of the instrument. We can usually only play notes spanning about four octaves; by contrast, it’s easy to play seven octaves apart on an 88-key piano.

What are some other things that are different about the guitar and the piano?

Well, for starters, the piano has a sustain pedal; you could play an ascending major scale on the piano and have each note ring out continuously, which can produce a beautiful, mysterious-sounding harmony. This sort of thing isn’t generally heard or done on the guitar. Is there a way we can achieve this on the guitar? Using a combination of open strings and fretted notes, we can get close!

Here are a couple examples of how we can use open strings to get that “sustain pedal” sound while playing a scale.

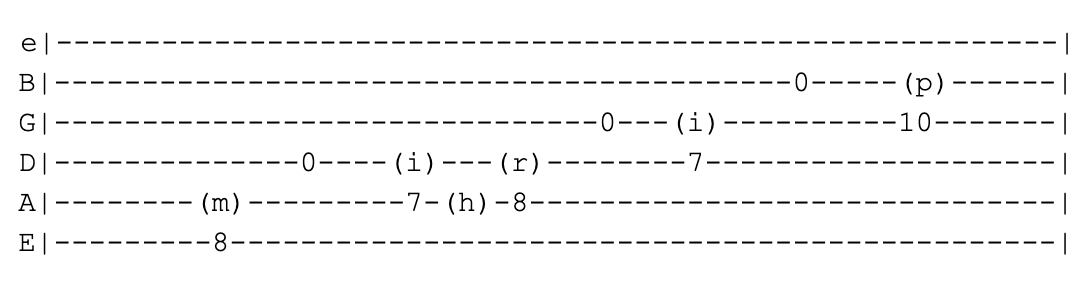

C MAJOR SCALE USING OPEN STRINGS IN ONE POSITION (ONE OCTAVE)

Read left to right, this is just an ascending C major scale in one octave: C D E F G A B C. The letters represent which finger to use (i = index, m = middle, r = ring, p = pinky). To really get the effect of gliding through the notes, try to hammer-on from E to F (7th to 8th fret on A string).

Here’s another example in the key of C, utilizing bigger stretches in the left hand and lower notes of the scale:

As you may be able to intuit, this approach to playing scales or melodies can easily be applied to open-chord-friendly keys, such as E major, D major, G major and A major – any key that contains the notes of the open strings. One of my favorite applications is using this concept in the key of B major:

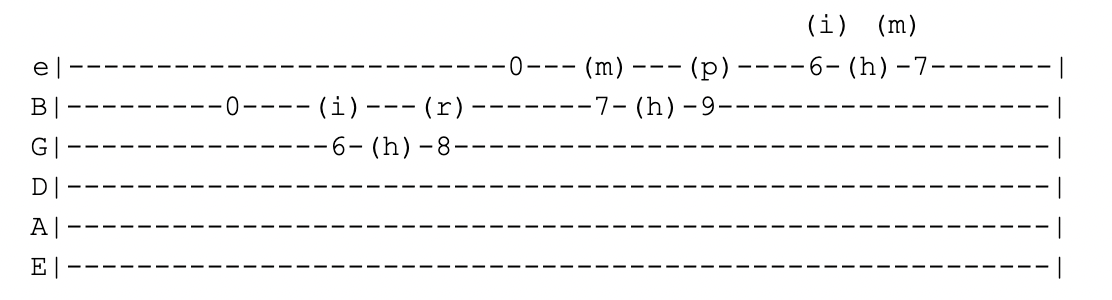

B MAJOR SCALE USING OPEN STRINGS IN ONE POSITION (ONE OCTAVE) (I) (M)

The trick is to arch the fingers of your fretting hand so that the open strings can ring, while also holding down the fretted notes on strings you’ve stopped playing. Again, hammer-ons and slides will really make this smooth and legato-sounding!

(For an additional creative challenge, the natural harmonic at the 7th fret of the low E string is the same B5 as the open B string, so you can use that instead of the B string if you want to really get that sustained ringing effect. The guitarist Bill Frisell, one of my favorites, is a master of using natural harmonics melodically to create this sort of ringing sustain that often sounds like more than one guitarist, or two instruments at once.)

On your own, try this out in other keys – there are only five distinct pitches covered by open strings (E, A, D, G, and B) so the fewer of those notes show up in a particular key, the less you will be able to use this approach without the use of capos or non-standard tunings. Another reason why exploring your options with this approach to playing scales is good is that it will improve your familiarity with the fretboard! After all, one of the unique characteristics of the guitar as an instrument is that there are multiple ways, all slightly different sounding, to play a specific pitch – the pitch of an open 1st string in standard tuning (E) can also be played at the 5th fret of the 2nd string, the 9th fret of the 3rd string, the 14th fret of the 4th string and the 19th fret of the 5th string!

Most importantly, have fun!

Tyler Bussey

I teach Banjo, Guitar, Bass Guitar. I primarily play the guitar, and also play the five-string banjo and bass guitar, among other instruments. I am well-versed in a variety of styles and techniques in addition to possessing a strong background in music theory. I’ve toured internationally and released records with bands that have been praised by Pitchfork, Noisey, and many other outlets and publications. I have a BA in English from the University of Connecticut.